Bluetooth, Unleashed: Classic, BLE and LE Audio in the Browser

The Web has evolved into a powerful platform for hardware interaction, yet Classic Bluetooth and LE Audio support have long remained one of the last frontiers trapped in native code. Breaking that barrier would open the door to a new class of connected Web experiences – connecting your Bluetooth headphones, sensors, and controllers directly through the browser, with no drivers, or system dependencies could enable innovation that isn’t gated by operating systems but fueled by open standards and creativity.

Bringing BTstack to the browser to include a complete Bluetooth Host stack addresses this gap. Our new port opens new possibilities for prototyping, testing, and deploying Bluetooth-enabled applications entirely from the Web, and all that while maintaining near-native performance.

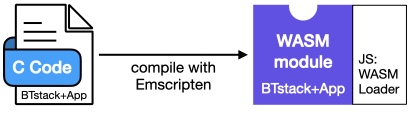

In the following, we will show our journey of how we leveraged WebAssembly (WASM) and Emscripten for embedding BTstack into the browser, as well as how we employed Web Serial to communicate with the Bluetooth Controller via the serial port.

Porting BTstack to WebAssembly

BTstack is designed to be flexible. While the core Bluetooth protocol and profile implementations are platform‑independent, the integration with a new platform is achieved by providing a minimal set of platform‑specific abstractions: run loop (i.e. timers + events), transport (e.g. UART), and persistent storage (e.g. pairing information). Beyond these core abstractions, porting BTstack also involves integrating with your build system, configuration of the stack (chipset, HCI transport, run loop), and building example applications to validate the port.

To bring BTstack to the browser, we’ll use WebAssembly (Wasm) rather than re-implementing the entire Bluetooth stack in JavaScript :). WebAssembly is a fast, portable binary format that allows code written in many languages to run efficiently and securely in web browsers and other environments, while integrating smoothly with JavaScript — so we can run “native-style” Bluetooth logic in the browser without without sacrificing security or performance.

Porting BTstack to the browser does introduce extra challenges: browser APIs are inherently asynchronous, and there’s no direct access to hardware, the file system, or traditional persistent storage. Still, BTstack’s lightweight design, built around a single-threaded run loop and a modular architecture, maps well to these constraints. Below is our agile, step-by-step approach, addressing the most critical tasks first:

- Prepare the Emscripten Build Environment

- Implement HCI Transport

- Enable C–JavaScript Interoperability

- Port the Run Loop

- Persistent Storage

- Audio and UI Support

Prepare the Emscripten Build Environment

These days almost any programming language can be compiled to WebAssembly. This process has been made significantly easier for C or C++ by the incredible Emscripten project, as it provides most of what you need to run code directly in the browser.

Since most of our recent builds use CMake — and Emscripten offers first-class support for it — we began with a minimal CMake project that simply compiles a basic printf("Hello World"). Emscripten supplies a custom CMake toolchain file at $EMROOT/cmake/Modules/Platform/Emscripten.cmake, which is already sufficient to compile C code to WebAssembly. In addition, Emscripten includes a built-in “shell”: an HTML page that loads and executes the generated WebAssembly module, providing console output in the browser.

This initial step was surprisingly easy and very rewarding. However, at this point we still miss the most critical part — that is, a way to communicate with the Bluetooth Controller via the serial port, i.e. access the Bluetooth dongle to send and receive raw HCI packets.

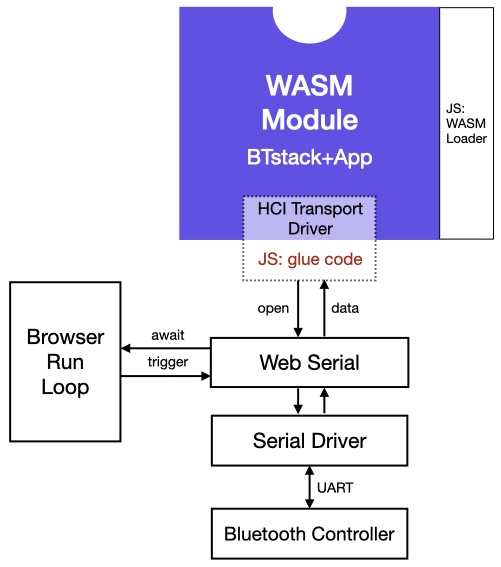

HCI Transport Layer

In BTstack, communication between the Host Stack and a Bluetooth Controller happens through an HCI transport driver. For most systems, our generic HCI H4 transport implementation, which handles packet framing, can be used directly with a custom UART driver.

Because C code compiled to WebAssembly runs inside the browser, it has no direct access to the file system or hardware interfaces such as serial ports. As a result, all communication with the Bluetooth dongle must go through JavaScript APIs provided by the browser.

For security reasons, JavaScript code cannot directly open a serial port. Instead, the Web Serial API requires an explicit user interaction: a method call triggers the browser to present a dialog in which the user selects the serial port to use.

Functionally, the Web Serial API is not very different from traditional serial port APIs. What initially caught us off guard, however, was that virtually all of its methods are asynchronous. Asynchronous interfaces are not new to us — most of BTstack’s APIs are asynchronous in general, too. In BTstack, a function returns immediately, and the outcome of the requested operation is later delivered to the higher layer via a callback provided by the caller. In contrast, any JavaScript Web Serial calls returns a so-called Future, which allows the caller to (a)wait the completion of the operation if needed.

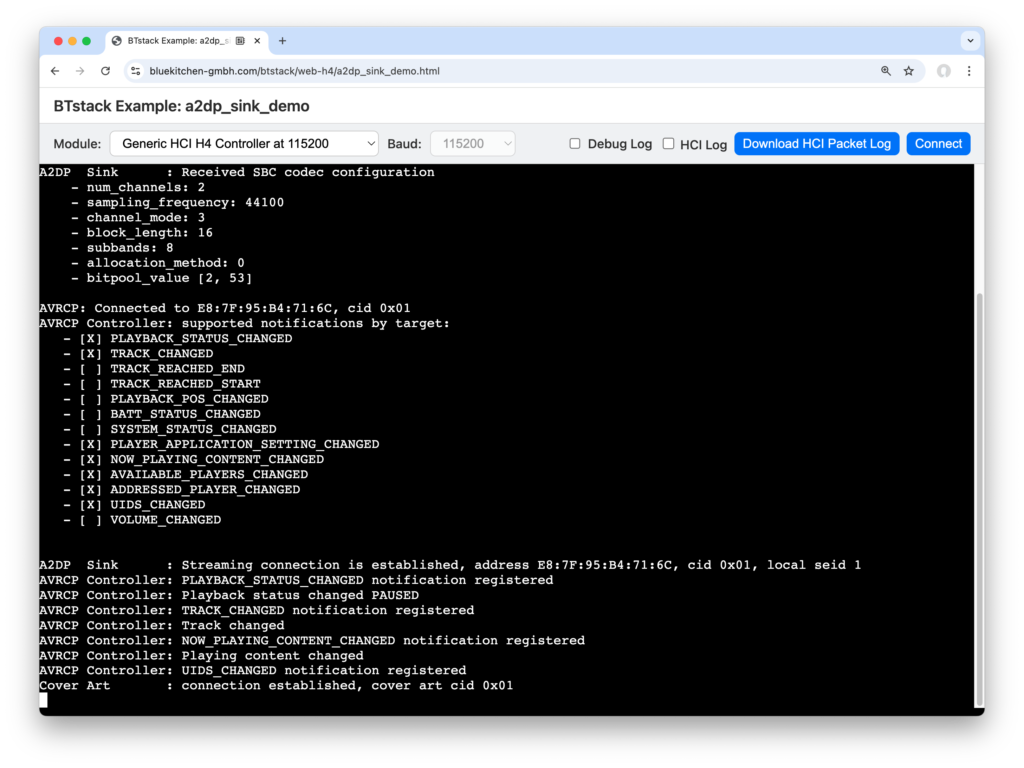

After getting used to JavaScript’s await syntax, we were able to open a serial port at 115200 baud, send an HCI Reset command, and receive the expected HCI Command Complete event — just as we would with any other serial port.

Once everything was working reliably at 115200 baud, we encountered another issue when trying to increase the baud rate for faster communication. Since the Web Serial API does not provide a changeBaudrate function, the only available approach is to close the port and reopen it with a different baud rate. While this is straightforward in principle, it conflicted with BTstack’s HCI Transport abstraction, which exposes only a synchronous setBaudrate function.

To avoid BTstack transmitting data at the original 115200 baud, while the Controller expects the new higher baudrate, we effectively needed to “pause” BTstack execution in the UART driver until the asynchronous JavaScript serial operations had completed. This is not possible for standard synchronous C code. Fortunately, the clever minds behind Emscripten had anticipated exactly this kind of problem. Emscripten’s Asyncify feature allows C code to suspend execution and await the result of an asynchronous JavaScript call — right in the middle of normal C control flow. While somewhat mind-boggling, this capability turned out to be the key to solving the baud-rate transition problem, without the need to change BTstack’s HAL to accommodate for that – which might be better approach in the long run though.

Interoperability between JavaScript and C

From C code, JavaScript code can be integrated in two main ways: either by inlining JavaScript directly into the C source, similar to inline assembly, or by invoking JavaScript code via the function emscripten_run_script. In our case, we relied exclusively on the first approach. Beyond simple inline snippets, Emscripten also provides the EM_JS macro, which allows you to define full-fledged JavaScript functions directly within a C file. While functionally equivalent to implementing these functions in a standalone .js file, this approach is often easier to maintain for the glue code needed for C–>JavaScript interoperability.

Because a C function is compiled into a WebAssembly function, it can also be called directly from JavaScript, if the calling conventions are adhered to. At a high level, scalar types and floating-point values map directly between the two worlds, while pointers are passed as plain integers, an important detail that becomes relevant later.

Another interesting aspect was determining how to efficiently pass received HCI packets from JavaScript into the C code. While exploring Emscripten’s APIs, we realized that all static memory used by the C code is backed by a single JavaScript Uint8Array. This makes it possible to reserve a buffer for a single HCI packet in C and expose its address resp. offset into the memory array to JavaScript through a small set of C functions. The JavaScript serial driver can then store incoming data directly into this “C HCI buffer,” allowing the C code to consume the packet without additional memory copies.

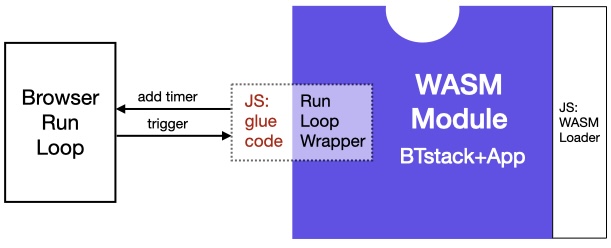

Run Loop Integration

Any Bluetooth Host stack requires support for timers (e.g. timeout during pairing) and needs to process incoming data from the Bluetooth Controller without blocking. Our Run Loop abstraction provides the necessary functionality to abstract from the actual platform.

In contrast to e.g. an embedded system, where our default btstack_run_loop_embedded.c is implemented by a simple while(1) loop, the browser already provides its own run loop, where BTstack cannot takeover full control – at least not without blocking the user interface. Instead, timer callbacks as well as data processing from the UART need to be handled in a callback fashion, where BTstack will be called whenever a timer fires or when there is new data to process.

While the details on how to implement such a scheme are very platform specific, the browser environment turned out to be very compatible and easy to integrate with. In our implementation for the function btstack_run_loop_add_timer(..) that registers a callback some time in the future, it is sufficient to call the web API setTimeout() with a JavaScript function that executes the timer when it fires.

Similarly, to process incoming UART data, it was sufficient to implement the function hci_transport_h4_js_receiver that runs as an infinite loop: it waits until a complete HCI packet has been received, forwards it to the stack, and then continues waiting for the next packet. Since JavaScript engines in browsers are single-threaded by default, this model fits perfectly with BTstack’s single-threaded mode of operation.

With BTstack successfully compiled to WebAssembly and serial port access established through the Web Serial API, the stack was able to start up fully. What remains are a number of smaller still necessary details to complete the integration.

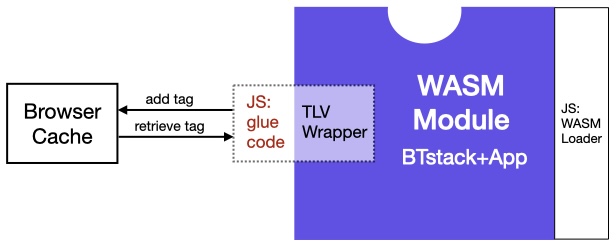

Persistent Storage

One of the remaining pieces is support for persistent storage. BTstack includes APIs for storing link keys, device database entries, and other persistent state that are based on a common Tag-Length-Value abstraction (TLV). On many embedded platforms there is no generic filesystem, so porting requires implementing these storage APIs using whatever nonvolatile memory your platform provides.

Fortunately, browsers provide the LocalStorage API, which offers a similar key–value storage backed by the browser’s cache. To make use of it, all that was required was a mapping our 32-bit tags to string-based keys. We implemented this by encoding each tag using the format TAG-<8 character hex value>.

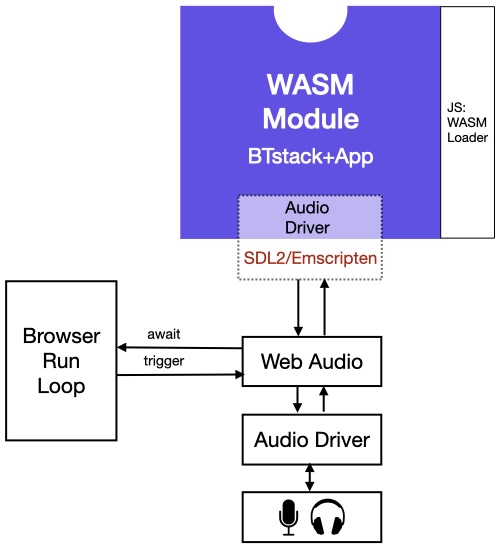

Audio

Similarly, some of the examples include audio playback. While this could be implemented using the Web Audio API via JavaScript, that API is quite flexible and somewhat complex. It is also rarely used outside the Web ecosystem. Instead, we discovered that Emscripten provides built-in support for the audio and graphics framebuffer APIs of SDL2. Since SDL2 is a also widely used on embedded Linux systems, we chose to implement our BTstack Audio API on top of SDL2. This approach allows the same implementation to be reused across different platforms and contexts.

Terminal xterm.js

Now we are getting closer to the user. While the Web is inherently UI-rich, our basic examples focus on a simple console to maintain portability across platforms. Emscripten provides basic console output, but it tends to be rather slow. A quick Internet search led us to xterm.js, a terminal emulator that performs as fast as a native terminal on macOS or Linux. Integrating it with Emscripten was straightforward: we only had to implement the Module.print(..) function in JavaScript to forward output to the xterm.js component.

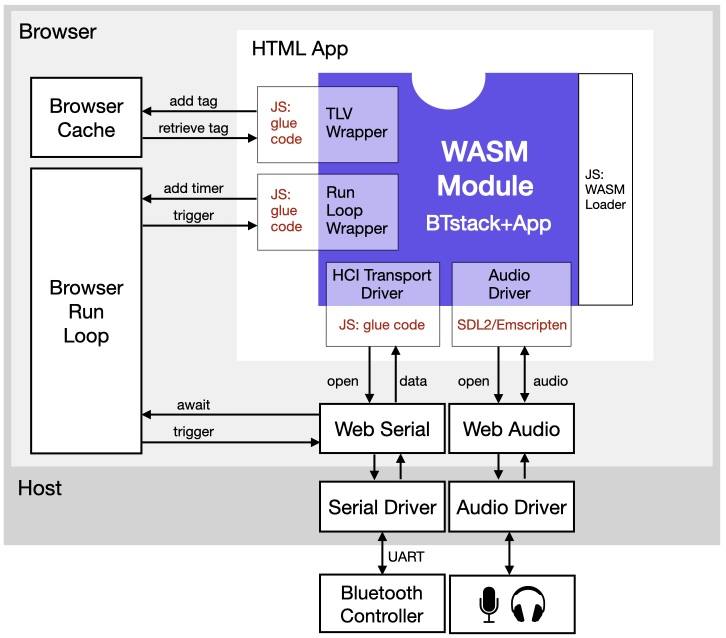

Complete Port

Putting all the steps and diagrams into a single picture, our browser port looks like this:

Lessons Learned

Porting BTstack to run in the browser via WebAssembly required navigating a series of architectural mismatches between native C code and the Web runtime. Browser sandboxing prevents direct access to hardware, storage, and serial ports, forcing all interaction through a user-mediated, asynchronous JavaScript API. This clashed with one of the few synchronous BTstack’s function calls, particularly for UART baud-rate changes, and ultimately required deeper integration techniques such as Emscripten’s Asyncify to suspend C execution across asynchronous boundaries. Efficient C–JavaScript interoperability demanded a solid understanding of calling conventions and Emscripten’s shared memory model to avoid unnecessary data copies. Additional adaptations were needed for persistent storage and audio output, leading to the use of the browser storage API and the use of the portable SDL2 framework to maximize reuse across web and non-Web platforms.

| Challenge | Description | Solution / Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Browser Sandboxing | WebAssembly cannot access hardware, serial ports, or file systems directly. | All interactions are done through browser-provided JavaScript APIs. |

| Serial Port Access | Serial ports require explicit user selection for security reasons. | Use the Web Serial API, which triggers a browser dialog to let users select the port. |

| Baud-Rate Reconfiguration Constraints | The Web Serial API lacks a changeBaudrate function and the alternative is to first close the port and then re-open it at the new speed. There functions are asynchronous, however BTstack’s HCI Transport abstraction expects a synchronous baudrate change function. | Use Emscripten’s Asyncify to suspend C execution until the asynchronous JavaScript calls have been completed. |

| Efficient Cross-Language Data Transfer | Moving HCI packets between JavaScript and C incurs extra memory copies. | Reserve a buffer in C and let JS directly write into it via Emscripten’s Uint8Array. |

| Persistent Storage Without a Filesystem | WebAssembly cannot use files for saving state. | Use browser LocalStorage. Map 32-bit tags to string keys like TAG-<8-character hex>. |

| Audio API Portability | Web Audio API is complex and web-specific. | Implement BTstack Audio API using SDL2 via Emscripten, enabling reuse on multiple platforms. |

| Fast, Portable Console Output | Emscripten’s built-in console output is slow, limiting usability of console-based examples. | Integrate xterm.js, a fast Web-based terminal emulator. |

Give It a Try!

Currently, we do not support loading the PatchRAM on Broadcom/Cypress/Infineon Controllers or configuring Realtek Controllers. As a result, only Controllers that provide standard HCI out of the box are compatible at the moment. We recommend trying either Ezurio’s Vela IF820 development kit with Infineon’s CYW20820, which can be flashed with an HCI firmware, or a Nordic nRF5x using our HCI UART bridge.

Outlook

With the state-of-the art Infineon AIROC CYW55310 now readily available in Ezurio’s Vela IF310 module, we plan to provide our LE Audio Demos in an easy-to-use Web version. Additionally, as we continue work on our internal “Box Demo” – see ESP32 LE Audio Blog post – we are curious to explore whether the complete demo, which uses LVGL for the UI, can run in a Web browser via LVGL’s SDL2 backend.